The Saga of Sefarad

Jewish Heritage Alliance is proud to announce a first of its kind platform dedicated to capturing the Saga of the Jews of Sefarad. We embrace this far-reaching and compelling story in all its complexities. From the early arrival of Jews to the Iberian Peninsula, to the "Golden Age", one of the greatest periods of Jewish history, a period of immense achievements, followed by the tragedies of the massacres and Inquisition where hundreds of thousands of Jews were forced to convert to Christianity (Conversos; Marranos; Crypto Jews) or be killed.

We continue to follow in the footsteps of those who fled to many parts of the world, creating Sephardic and Converso communities in such far-flung places as Palestine, Greece, Amsterdam, the Caribbean and North and South America. To this day, descendants of those expelled Jews still speak Judeo-Spanish, or Ladino, 15th-century Spanish with traces of the local languages of the countries in which they settled. This was a watershed moment in the annals of Jewish and world history. Yet for all of its significance and relevance this segment of history receives scant attention compared to other consequential Jewish historical events.

The victorious rulers of Spain and the Church thought they scored a great "triumph" in its expulsion of the Jews from Spain and forcing hundreds of thousands of Jews to convert to Christianity. But this "triumph" was not to be and in effect signaled the unraveling of the power of the Church and ushered in the beginning of the Renaissance.

Arrival of Jews to Spain

It’s difficult to pin-down the exact time when the Jews first arrive in Spain. There are hints from the Bible that the lands of the western Mediterranean were well known to the Israelites. Around 970 BCE Solomon formed an alliance with Hiram of Tyre, the king of the Phoenicians, providing Hiram with sailors. The territories of the Israelite tribes of Asher, Zebulon, and Dan were part of Phoenicia and some early Spanish Jewish documents actually refer to those tribes as having descendants living in Iberia. The population of Hispania (the ancient name of the Iberian Peninsula) was ethnically diverse; even in pre-Roman times.

The Golden Age for the Jews to Spain

The golden age of Jewish culture in Spain coincided with the Middle Ages in Europe, a period when Muslims ruled much of the Iberian Peninsula. In the 8th century, the Berber Muslims (Moors) swiftly conquered nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula. Under Muslim rule, Spain flourished, and Jews and Christians were granted the protected status of dhimmi. While not offered equal rights with Muslims, during this “Golden Age” Jews rose to great prominence in society, business, and government. The Jews flourished in business, fields of astronomy, philosophy, math, science, medicine, and religious study. This period also witnessed a resurgence of Hebrew poetry and literature from a traditional and liturgical language to a living language able to be used to describe everyday life. The intellectual achievements of the Sephardim (Spanish Jews) enriched the lives of everyone, including non-Jews. In the early 11th century, centralized authority based at Cordoba broke down following the Berber invasion and the ousting of the Umayyad Dynasty. The disintegration of the caliphate expanded the opportunities to Jewish and other professionals. The services of Jewish scientists, doctors, traders, poets, and scholars were generally valued by the Christian as well as Muslim rulers of regional centers, especially as recently conquered towns were put back in order. Jews took part in the overall prosperity of Muslim Al-Andalus. Jewish economic expansion was unparalleled. In Toledo after the Christian reconquest in 1085, Jews were involved in translating Arabic texts to the romance languages in the so-called Toledo School of Translators, as they had been previously in translating Greek and Hebrew texts into Arabic. Let us summarize that this period saw the rise of influential Jewish personas, including Abd al-Rahman's court physician and minister was Hasdai ibn Shaprut, a Jewish scholar, physician, diplomat, and patron of science. Also Menahem ben Saruq, Jewish lexicographer and poet who composed the first Hebrew-language dictionary, a lexicon of the Bible; earlier biblical dictionaries were written in Arabic and translated into Hebrew. Samuel ibn Naghrillah (Samuel HaNagid), a medieval Spanish Talmudic scholar, grammarian, philologist, soldier, merchant, politician, and an influential poet. The most well-known persona of the period is Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, commonly known as Maimonides, and also referred to by the acronym Rambam, was a medieval Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah scholars of the Middle Ages.

Yet, despite the Jews’ success and prosperity under Muslim rule, the Golden Age of Spain was not without pogroms and massacres. The golden Age was interrupted by periods of oppression of Jews and non-Jews. The downward trend was ushered in with the death of Al-Hakam II Ibn Abd-ar-Rahman in 976 (was the second Caliph of Córdoba). The Caliphate began to dissolve, and the position of the Jews became more precarious under the various smaller Kingdoms. The first major persecution was the 1066 Granada Massacre when a Muslim mob stormed the royal palace and crucified the Jewish vizier (a high-ranking political advisor or minister) also Joseph ibn Naghrela, a vizier to the Berber King Badis al-Muzaffar of Granada, and the leader of the Jewish community. They massacred much of the Jewish population of the city. More than 1,500 Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons were killed just one day. In 1090 the situation deteriorated further with the invasion of the Almoravids, a puritan Muslim sect from Morocco. The Almoravids, were ousted from the peninsula in 1148 but it was invaded again by even more puritanical Almohad Caliphate or "the unifiers", a Moroccan Berber Muslim movement founded in the 12th century. During the reign of these Berber dynasties, many Jewish and even Muslim scholars left the Muslim-controlled portion of Iberia for the city of Toledo that was reconquered in 1085 by Christian forces. But in 1391 intense, pent up anti-Jewish sentiment in Christian Spain erupted with great violence against the country's prosperous, well-established Jewish community. Spanish cities were engulfed in ferocious pogroms that destroyed much property and claimed many lives. The final “blow” came in 1492 when the Jews were forcibly expelled by the Edict of Expulsion by Christian Spain in 1492 and a similar decree by Christian Portugal in 1496.

Pogroms, Inquisitions and Conversos

In the 14th century, the bubonic plague, the Black Death, ravaged Europe – including the Jews who, on top of everything else, were blamed for causing it! The 14th century also marks the middle of the end for Spanish Jewry. The final end of Spanish Jewry will come in 1492, but the middle of the end is in 1391. That year James II of Aragon passed a law, under the pressure from the Roman Catholic Church, that they no longer would abide Jews in Spain, dominated by the kingdoms of Castile, Granada and Aragon. Jews living there were given the choice of conversion, death or emigration. A number of pogroms followed that law. For 400 years, the Jewish community of Barcelona had served as the center of Judaism, and had been headed at various times by such luminaries as Nachmanides and Rabbi Solomon ben Aderet (Rashba). Yet, all of its 23 synagogues were burned to the ground. By 1394, the Jewish population ceased to exist there. Similarly, major Jewish communities such as Seville, Toledo, Perpignan (Kingdom of Majorca, Catalan Region) were all destroyed in 1391. Nevertheless, the Jews still held enough power, wealth and influence to bribe the king and stay the order for 100 years.

At this time, Christianity mounted its most massive offensive in history to convert Jews. It became an obsession of the Church. At the head of this drive were apostate Jews. Rabbi Solomon ha-Levi was a famous rabbi who was originally from Seville and who rose to prominence in the court of the king. He was a noted Talmudist, one of the great rabbis of his time and commanded the respect of the Jewish community. After the pogroms of 1391, he converted to Roman Catholicism along with his wife and children (Some say his wife did not convert and remained faithful to Judaism to the end of her life). He converted publicly and took on the name, Paul of Burgos. In 1394, he obtained an appointment to Cardinal Pedro de Luna, who later would be Pope Benedict XIII. He took it upon himself, as converts are wont to do, to explain the matter to his former brethren. We can get a glimpse of the confusion of the times from situations and question posed to the rabbis: A husband remains Jewish, and his wife who remains Catholic takes him the Inquisition. Or a wife remains Jewish and she takes the husband who was becoming Catholic to the Jewish court to give her a divorce, or they wrangle over the children. Children brought their ancient parents in front of the Inquisition to force them to convert. These types of cases show us how heart-wrenching and pervasive the problem was. Paul of Burgos made sizable inroads in the Jewish community of Spain. At the time, in the late 1300s to the early 1400s, one of the most famous rabbis in Spain was Hasdai Crescas. He stood in the breach as the main defender and protagonist of Judaism. He was the teacher of all of the great rabbis of his time, including Solomon ha-Levi before his apostasy. A disciple of both Hasdai Crescas and Solomon ha-Levi, Joshua ha-Lorki, also converted to Christianity. These two apostates worked together and converted 50 leading Jewish intellectuals, who then proceeded to sign a document addressed to the fellow Jews which in effect said that it was nonsense to resist Christianity; the only way for the Jewish community to survive in Spain was to convert. This created a wave of momentum toward conversion.

Hasdai Crescas attempted to reverse the momentum with a book called Ohr Hashem, “The Light of God.” This was actually the first of a new genre of books that defending Judaism and even attacked Christianity with greater audacity as time went on. Shortly after Hasdai Crescas’ Ohr Hashem was published, a second influential book was penned by Rabbi Isaac ben Moses ha-Levi Duran (also known as Profiat Duran) called Ma’aseh Efod. Both books attacked Christianity. The more successful Christianity was in obtaining conversions the stronger the reaction of the Jews in mounting a counter-offensive against it. For about 100 years there was a no-hold-barred polemic between Jews and Christians, the Jews saying things they never dared say before or since about Christianity. This book led to an even stronger book Kelimmat ha-Goyim, “The Shame of the Gentiles.” These books had a tremendous effect upon the Jews and almost turned the tide. He expressed things other Jews felt but were afraid to say living under Christian domination. At the same time, the book unleashed a wave of anti-Semitism. In the medieval world it was not merely risky to ridicule Christianity, but a crime punishable by death. The fact that the book appeared at all made the entire Jewish community in Spain culpable in Christian eyes, and justified the harshest persecutions. One leader of the Jew-baiters claimed to have initiated pogroms that converted 20,000 Jews and slew 10,000. In his eyes, that was his ticket to Heaven.

Thus began a century of conflict between Jews and non-Jews that culminated in the mass expulsion of all Jews from Spain in 1492. (Ten years later, the Muslims were likewise driven out.) In their edict of expulsion, issued on March 31, 1492, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella announced their "decision to banish all Jews of both sexes forever from the precincts of Our realm." Ordered, on pain of death, to leave within four months, the Jews were permitted to take their personal belongings, except for gold, silver, coined money, or jewels. Estimates of the number of Jews banished generally range from about 165,000 to 400,000. An estimated 50,000 Jews chose baptism to avoid expulsion. In his diary Christopher Columbus noted: "In the same month in which Their Majesties issued the edict that all Jews should be driven out of the kingdom and its territories, in the same month they gave me the order to undertake with sufficient men my expedition of discovery to the Indies."

Beginning in 1412, anti-Jewish laws began to appear in northern Spain. The Jews were:

• Not to be confined into separate quarters in all cities and villages

• Not to differentiate themselves from Christians by their more modest mode of dress

• Not to not wear garments of either silk or satin, or have “feathers in their heads”

• Not to let their beards grow long and not be perfumed

• Not be called by Christian names or addressed by any title

• Not engage in farming, hold posts in the government or to be physicians, pharmacists, blacksmiths, tailors or shoemakers

• Not serve Christian customers (for example, if one was a Jewish artisan)

• Not act as brokers or money-changers on behalf of Christians.

What were the Jews permitted to do? Be “hewers of wood and drawers of water.”

This system of laws struck at every aspect of Jewish life. Consequently, 1412 marks the beginning of large-scale emigration of Jews from Spain begins. Over the next 80 years a quarter of a million Jews would leave Spain.

The two Jewish apostates, Solomon ha-Levi and Joshua ha-Lorki, spoke to Pope Benedict and convinced him to force a debate between the leading Jews of Spain and themselves – with pope as the referee (to make it “fair”). If the Christians won, then all the Jews would have to convert; if the Jews, then they could remain Jews. It was a great idea to the Pope. To the Jews, it was a disaster, but they had no choice. It was not really a debate because the Jews were not allowed to present a case; to do so would be insulting the Church. This debate took place at Tortosa in 1413, and lasted almost three years. In total, at one time or another over 300 rabbis participated in the debate. Over 100 of the rabbis, one third of those who participated, converted to Christianity. It was debacle for the Jews. It is hard to have a handle on the times, but it is obvious that the Jews were subjected to such a hounding, such shameful behavior and pressures, that only the very strong could withstand it. When the debate ended it was clear that the Jewish community in Spain was coming to an end. When you add it that the Black Death came to Spain as well, and it came twice, you realize the position of the Jews held no hope. Many of the Jews in Spain realized it and got out now.

The Inquisition in Spain has started in earnest and took on full force. There were Jews who had converted to Christianity and reverted to Judaism. It was against them that the Inquisition took out its vengeance and committed its worst excesses. People, under torture, testified that they had seen others light candles on Friday night or eat unleavened bread (matzah) on Passover. Everyone informed on everyone else. The trials of the Inquisition were called “Acts of Faith,” but the cruelty of these acts was just unspeakable. After the tortures, the guilty were publicly burned at the stake. Over time, the Inquisition grew in cruelty as well as in the numbers of Jews who were involved. At the same time, it became counter-productive toward Christian purposes, because many Jews who might have considered converting did not do so now for fear that the Inquisition might get to them one day too. The Christian who was suspected of being Jewish was far worse off than the Jew who never converted.

By the late 1400s, the Inquisition was headed by a man named Tomás de Torquemada. He had an almost mystical hold over the royal household in Spain, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, both of whom were fervent and fanatical Catholics. Torquemada was their personal confessor. He was convinced that only through the conversion of the Jewish people in Spain would he, Ferdinand and Isabella fulfill the task that God had set before them. Paradoxically, Ferdinand’s and Isabella’s kingdom, Castile, had Jews highly placed in the government. The three leading Jews in their government were Don Abraham Senior, Don Meir Melamed (his son-in-law) and Don Isaac Abarbanel (also spelled Abravanel and commonly referred to as The Abarbanel). Among his accomplishments, The Abarbanel was a noted warrior, a general in the Spanish army. Having seen the excesses of Spain, he and his father fled to Portugal in the 1480s and rose to a very high office. But then there was a rebellion of noblemen against the king and they accused Abarbanel and his father of being part of the rebellion. Forced to flee, they returned to Spain where they were employed in the court of Ferdinand and Isabella. The Abarbanel was again employed as a general in the army and as the Minister of Finance. There is strong suggestions that the idea of Christopher Columbus expediting was at the behest of The Abarbanel. It certainly went through him technically as the Minister of Finance. It would be one of the great ironies in history if it was.

Expulsion of the Jews from Spain

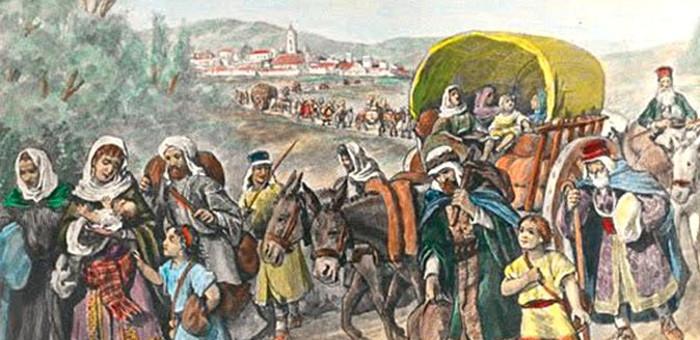

The Golden Age on the Iberian Peninsula lasted about a millennium until the pogrom of 1391 when many of Spain's Jews were forced to convert to Christianity (Conversos; New Christians; Marranos; Crypto Jews). In 1491, the king proclaimed that the 100 year stay on the Edict of Expulsion Decree against the Jews was officially over. All Jews would have to convert or be killed. So many of the remaining practicing Jews chose to join the already large Converso community rather than face exile. Those Jews that opted for exile rather than conversion took their wandering backpack, left everything behind, bravely and tenaciously journeying as refugees into the unknown. Our platform follows in their footsteps and allows you to discover, firsthand, how these intelligent, cultured, and industrious people, flourished and created the new world. The remaining Jews who had chosen to remain practicing Jews were finally expelled during the Alhambra Decree in 1492. Interestingly Don Abraham Senior, Don Meir Melamed and Don Isaac Abarbanel, as the king’s Jews, were exempt from the decree.

The Abarbanel attempted to have the edict of expulsion cancelled and told the king that economically and socially it was a very foolish step to expel the Jews. Spain was beginning its struggle with England for world dominance. It was the wrong time for such an upheaval, he told the king. All these reasons began slowly to sink in. According to legend, King Ferdinand was ready to give in. At that moment, however, Torquemada rushed into the room holding a crucifix, and said, “Will you crucify him a second time for 30 pieces of silver?” The ploy worked and Ferdinand said that under no circumstances would he stay the decree. The Abarbanel refused the king’s exemption, saying that he would share their fate of his people. Unfortunately, the other Court Jews did not follow him. They and their family lines disappeared from the Jewish people. The decree was set for the ninth day of the month of Av (Tisha B’Av), August 9, 1492. That, in God’s irony, was the day Christopher Columbus set sail to discover the New World. Columbus wrote in his log that his ships had a very hard time clearing the harbor because all the ships had been hired by the Jews who had to leave Spain that day. Overall, 250,000 Jews left Spain while about that same number remained and converted to Christianity.

Many of the 250,000 who remained tried to practice Judaism in secret and would be called Marranos, the “secret” Jews. But within 60 years they disappeared. First, they were persecuted fiercely by the Inquisition. Second, Judaism is almost impossible to keep in secret. It is not surprising that many historians and social scientists say that almost everyone in Spain has Jewish blood somewhere along the line. It is said that the late General Francisco Franco, the dictator in Spain during World War II – a firm and almost fanatical Roman Catholic — was of Jewish blood. That is why he never turned over one Jew to his erstwhile ally, Hitler, and never entered the war.

The end of Spanish Jewry was a blow unequaled until the Holocaust. It raised all of the terrible questions of the exile, all the “whys” for which there are no answers. They had no homes. Wherever they came they were not welcome. Many of their ships were captured and destroyed by pirates. It is estimated that another 25,000 died leaving Spain. Where did they go? Most stayed in the Mediterranean basin, among their Sephardic Jewish brethren. Many returned to North Africa: Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Many went to Italy. The Abarbanel returned to Portugal, but in 1496 the Inquisition forced the king there to also expel all the Jews. He then moved to Italy and there wrote many of his major books. In a bitter aside, he made the comment what a waste it was that he spent all that time and effort making contributions to Spain and Portugal. If only he could have put all those efforts into Torah. What a personal tragedy it was, he wrote. Today, The Abarbanel is remembered among the Jewish people for his classical works in Torah. His monument is in the schools of learning and hearts and minds of the Jewish people who study his works and comment upon them. He himself realized that. It was his final epitaph. In that regard, he is a symbol for all Spanish Jewry and what it meant.

Jews and Discovery of the Americas

Among the various discoveries of the fifteenth century, none is more intimately connected with the Jews and their history than the discovery of the New World. Indirectly and directly, the Jews contributed to the success of Columbus' voyage of exploration: indirectly, by means of several astronomical works; and directly by the invention of instruments for astronomical observation.

Another conspicuous items in the discovery of America was provided by the Marano Luis de Santangel who was originally a Jew, later baptized and eventually became finance minister to King Ferdinand II who persuaded Queen Isabella to support Christopher Columbus' voyage in 1492. He represented to Queen Isabella the advantages that would accrue to the crown and to Spain from the discovery of a sea-route to the Indies—immeasurable riches, accession of lands, and immortal fame. Under the influence of such glowing representations, she consented to Columbus' undertaking, and, since the state treasury was exhausted, was ready to pawn her jewels to procure the necessary funds to fit out his expedition. At this stage, Santangel sought permission to advance the necessary sum out of his private treasure and loaned the royal treasury 17,000 ducats (about $20,000; perhaps equal to $160,000 at the present day) and did so interest free.

On August 2, about 300,000 Jews (some writers consider the number much greater) left the country; and on the next day, Friday, August 3, Columbus sailed with his three ships in quest of the unknown. Among the members of the expedition several were of Hebrew blood. Of these there may be mentioned Luis de Torres, who understood Hebrew, Chaldaic, and some Arabic, and who was to serve the admiral as interpreter; Alonzo de la Calle, who took his name from the Jewish quarter (calle), and died in Spain in 1503; Rodrigo Sanchez, of Segovia, who was a relative of the chancellor of the exchequer, Gabriel Sanchez, and joined the expedition in compliance with the special request of the queen; the surgeon, Marco; and the ship's doctor, Abraham Nunez Bernal, who had lived formerly in Tortosa, and had been punished in 1490 by the Inquisition, in Valencia, as an adherent of Judaism. There is also a growing discussion regarding Columbus true identity with suggestions that he was a converted Jew.

But there is anecdotal discussion (not solid proof) by Cyrus H. Gordon, professor of Mediterranean Studies at Brandeis, suggesting ancient Hebrews reached America 1300 years before Columbus. He theorizes that Hebrew refugees fleeing Roman oppression crossed the Atlantic, perhaps with the aid of Phoenician navigator and eventually settled in Tennessee and Kentucky. He based his theory by a stone uncovered in a Tennessee Indian burial mound claiming that inscriptions on the stone are ancient Hebrew characters that say "for the land of Canaan."